September 1, 2013

Better profits — Part 2:

Beware the bottleneck

BY MARK BRADLEYIf there was one simple number you could use to help make better business decisions consistently, wouldn’t you want to know it?

There are thousands of numbers and indicators that give you feedback on your company or your jobs. Gross profit, net profit, sales by month, sales per customer, sales by salesperson, revenue per hour, overhead ratio, and many more. They are all worthwhile metrics; however, every company has one simple metric they should be focused on, and here’s why.

Picture a simple assembly line that makes cars. Our line has four stations:

Frame and body assembly [30]In brackets, beside each station, is the number of cars that can be completed per hour. The paint booth, for example, can paint 35 cars per hour.

Paint booth [35]

Engine and drive-train assembly [15]

Finishing and quality assurance [55]

Looking at our line, the maximum number of cars we can build – start to finish – is 15 per hour. It doesn’t matter that we have enough finishing and inspecting capacity to do 55 cars an hour, or that we can assemble 30 frames per hour; we can only assemble 15 engine and drive-trains per hour and, therefore, we can only build and sell 15 complete cars per hour.

If you were the manager of this line, your job is obvious. You need to get more production out of your engine and drive-train section. You would likely be ready to invest sizeable amounts of money to improve station three, since enhancements there would directly increase total sales, without investment being required elsewhere. (We could produce and sell up to 30 cars per hour before we had to improve other stations.)

Somewhere in your landscape company exists this same weak link. It’s your own “engine and drive-train assembly” station. Picture your company like a funnel. Your funnel neck will only allow so much work through at once. Your company’s production/sales are limited by the amount of work that can pass through the thinnest portion of your funnel. It’s called your bottleneck.

Although there is no specific bottleneck that applies to every company in the industry, most companies share a common one. Skilled foremen, who can get jobs done independently on time and on budget, are the most common weak link in the landscape industry. Whether it’s a single owner-operator who can’t seem to pull back from daily operations, or a multi-national franchise that depends on many managers and foremen to hit sales targets, the bottleneck for most companies is the skilled people who can independently manage a job through to completion.

Therefore, sales per foreman-hour, or sales per owner-hour if you’re actively managing the field work, might be a single metric you could use to make better, more profitable decisions. It’s nice to know how the other stations in your assembly line are functioning, but your company’s success or failure is largely determined by your bottleneck.

Let’s take a look at how that metric would affect the way decisions are made in real life.

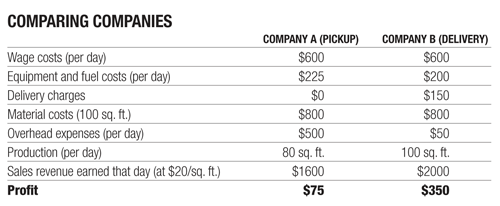

Let’s take a look at how that metric would affect the way decisions are made in real life.Picture two landscape companies. They each have stonemasons who install 100 square feet of stone each day. They have both agreed to do 100 square feet of stonework for $2,000.

Company A measures success by cost savings. Rather than spend $150 to have the stone delivered by the vendor, they send their foreman to pick it up. After all, two hours of wages is less than the $150 delivery charge.

Company B uses the bottleneck approach. They only have a few masons who can independently run a job. They look at the cost of the delivery, not based on the cost of the stonemason but on the overall cost to the company. Two hours of their stonemason picking materials is 20 square feet of stone that doesn’t get installed. At $20 per square foot, that’s a cost of $400. Company B gets the materials delivered and happily pays the $150 charge so their bottleneck, their foreman, stays focused on generating revenue (finished stonework).

Who comes out ahead?

The big difference is that company A spent a little more in fuel (to pickup the stone), but saved the delivery costs. However, they lost 20 per cent of their available production hours that day while they picked up stone. That loss of production cost them dearly. Not only are they far less profitable than company B, but company B will be finished and starting the next job sooner, giving them a further advantage.

Better profit lesson: The cost of working on non-revenue generating tasks is not the cost per hour of the bottleneck, it is the cost of lost company revenue.

Most landscape companies could improve profit by looking at owner/foreman-hours the same way. The best decisions are the ones that get the most production out of your bottleneck, even if it means it increases the cost of production (up to a limit, of course). Common examples where costs increase as do profits, include: getting your vendors to deliver; buying materials pre-processed to reduce prep time; buying or renting equipment to improve productivity; more detailed designs and project planning before the start of a job; and, using specialized crews — so specialized foremen are dedicated to tasks that require specialization.

Some old adages you may have heard, such as don’t buy equipment until you can pay for it in cash, are sound, conservative approaches to running a business. However, when you look at those decisions from the bottleneck point of view, they are not necessarily the most profitable.

The examples above increase sales — the upper half of our sales-per-foreman equation. But don’t stop there. You also need to look at the bottom half of the equation and focus on reducing foreman-hours spent on tasks that don’t drive revenue.

Take a hard look at your operations and see where you might offload non-billable tasks from your bottlenecks, so they can stay focused on production-related work.

- Washing trucks, maintaining equipment: Could this done by others – even outsiders?

- Picking up or moving materials: Can your vendors deliver? Would it make sense to have your own dedicated delivery truck?

- Waiting for instructions or planning: Could you spend more time designing or planning jobs to reduce questions/confusion/mistakes on your jobs?

- Loading/unloading vehicles/equipment and fuelling: Could an “evening” yard-person do this for all the trucks? Could you outsource your fuelling to a mobile fuelling company?

Where do you start? Here are a few places you can begin:

- Divide your job prices by estimated foreman-hours. Get a feel for the ranges of “good” and “bad” jobs (Hint: the lower the sales per foreman-hour, the worse the job).

- Ensure your payroll and jobcosting systems are linked. Every payroll hour should be tracked to a task, whether it is billable or not. It’s critical that you know how much time is spent unbilled.

Mark Bradley is president of The Beach Gardener and the Landscape Management Network (LMN), in Ontario. LMN provides education, tools and systems built to improve landscape industry businesses.