March 1, 2016

Taking the guesswork out of change

BY MARK BRADLEY In the last issue of Landscape Trades, we looked at how a company’s overhead changes during traditional growth phases. Countless dollars can be saved by understanding those phases and avoiding periods where it is very difficult to make a consistent profit.

In the last issue of Landscape Trades, we looked at how a company’s overhead changes during traditional growth phases. Countless dollars can be saved by understanding those phases and avoiding periods where it is very difficult to make a consistent profit.Now, with the start of a new year, we’ll examine how to use some simple numbers to manage expansion or contraction of your company and how to better ensure profits in times of change.

Start with a budget

Without a budget, you’re bound to learn how to manage growth and change from your mistakes. Those hard lessons sharpen your gut instincts, but it’s senseless to suffer through mistakes and financial hardship – or even just the stress of not knowing – when it could be avoided with a simple plan.Let’s use an extremely simplified budget to look for ways to make better decisions when it comes to growing or changing companies. We’ll use our old friend “Dan” from Danscaping as an example (Dan is a fictional character and any resemblance to an actual company of this name is purely coincidental).

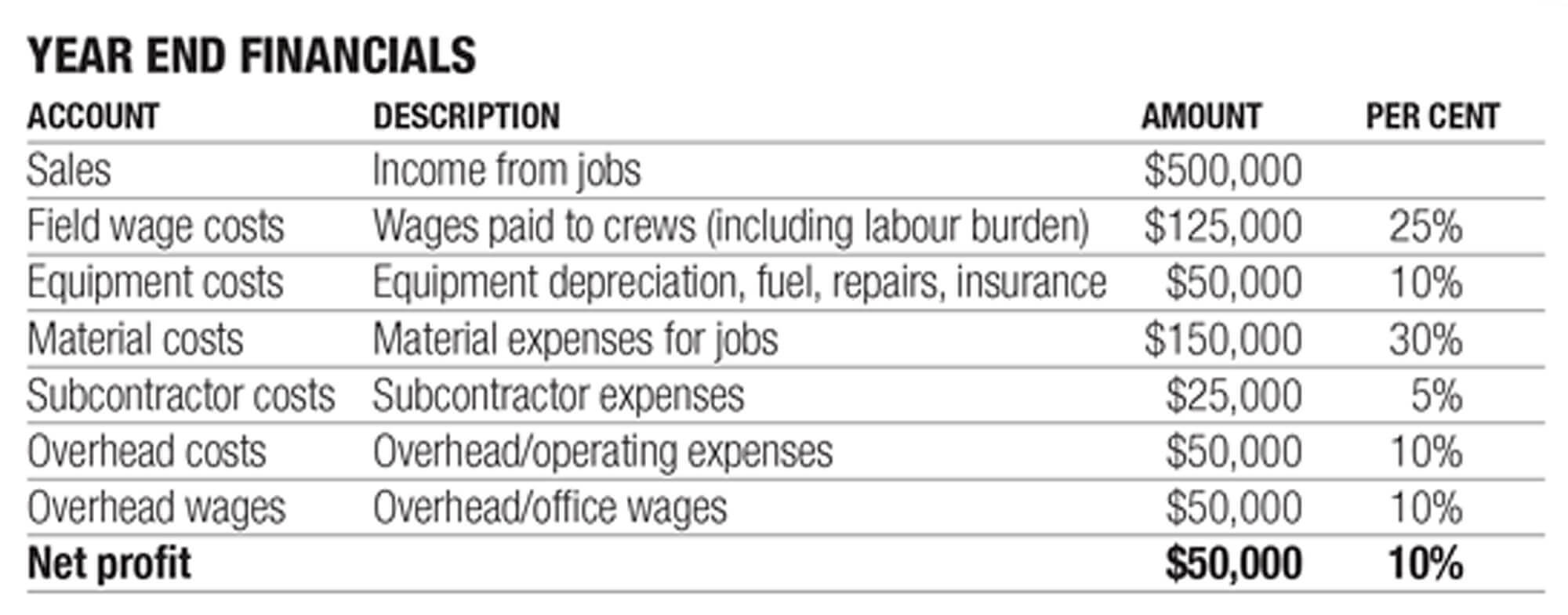

Dan’s financials at the end of the year are summarized below.

By all accounts, Dan had a strong year. He had a nice profit, lots of work, and is already booked up to July for the following year. He can’t wait to get started, but he can’t help but think that he’s got enough work coming in to keep another crew busy. There are a number of concerns Dan should consider, since adding another crew is a major investment that involves:

- Hiring more staff.

- Equipping another truck and trailer for this crew.

- Purchasing machinery.

- Adding administrative staff to handle the increase in bookkeeping.

Dan doesn’t have to just dive-in and hope. There is a story behind his numbers that will help him make the right decision.

Step 1: Assess the company

Dan wants to grow, but he wants to be conservative as well. He figures he could sell another $200,000 worth of jobs next year, conservatively, if he had the crew to do the work, so he starts his plan with a $700,000 sales goal; the same $500,000 he did last year, plus an additional $200,000.

Step 2: Assess the cost to hire

Dan’s crews are maxed-out right now, so he’s going to need to hire. He figures another two-man crew could do the $200,000 worth of work. He also figures he would need a foreman at $40,000 and a labourer at $25,000 for his new crew. After adding payroll taxes, workers compensation, unemployment insurance and other deductions, his total wage estimate is $75,000 for the new crew.

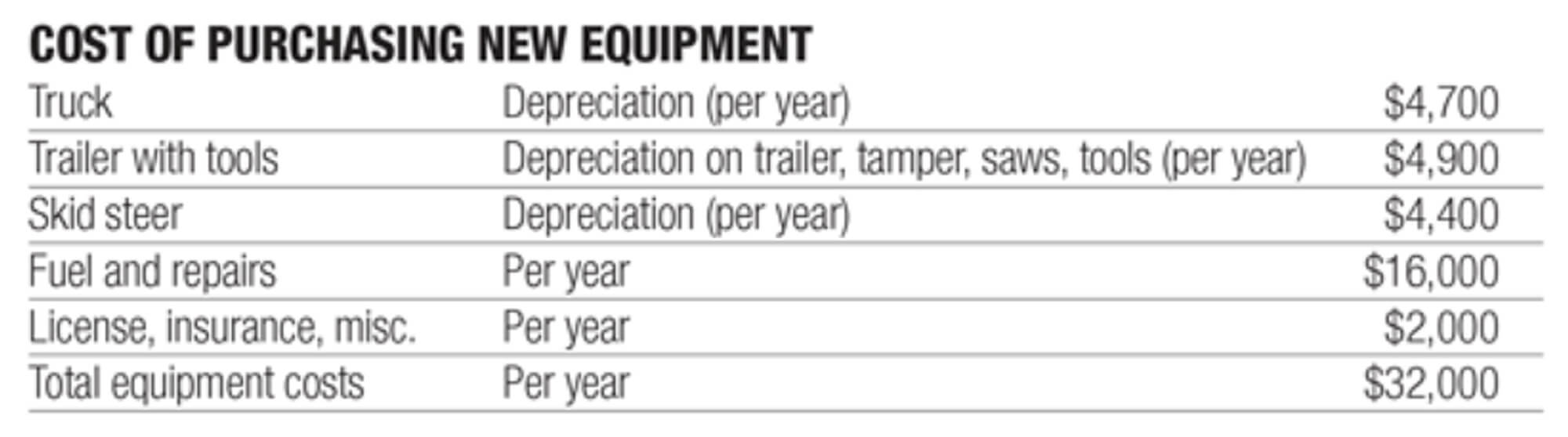

Step 3: Assess the cost of purchasing new equipment

Dan’s new crew is going to need a truck, a trailer and bunch of tools. He also might want to look into buying a second skid steer for them to use. Here is what his equipment is going to cost: (note, costs are realistic for typical trucks, trailers and skid steers, but are not guaranteed accurate for your company).

Step 4: Estimate material costs

Dan can use his material numbers from last year to help him predict whether his plan is going to work. Last year (see chart), he spent 30 per cent of his sales on materials. If he is going to do more of the same work with the new crew, he could expect to spend about the same. (Materials would change if his new crew was doing strictly maintenance, but in this case, Dan is doing more construction jobs). If Dan is going to add $200,000 in sales, he could expect to spend 30 per cent of that, or $60,000, on materials.

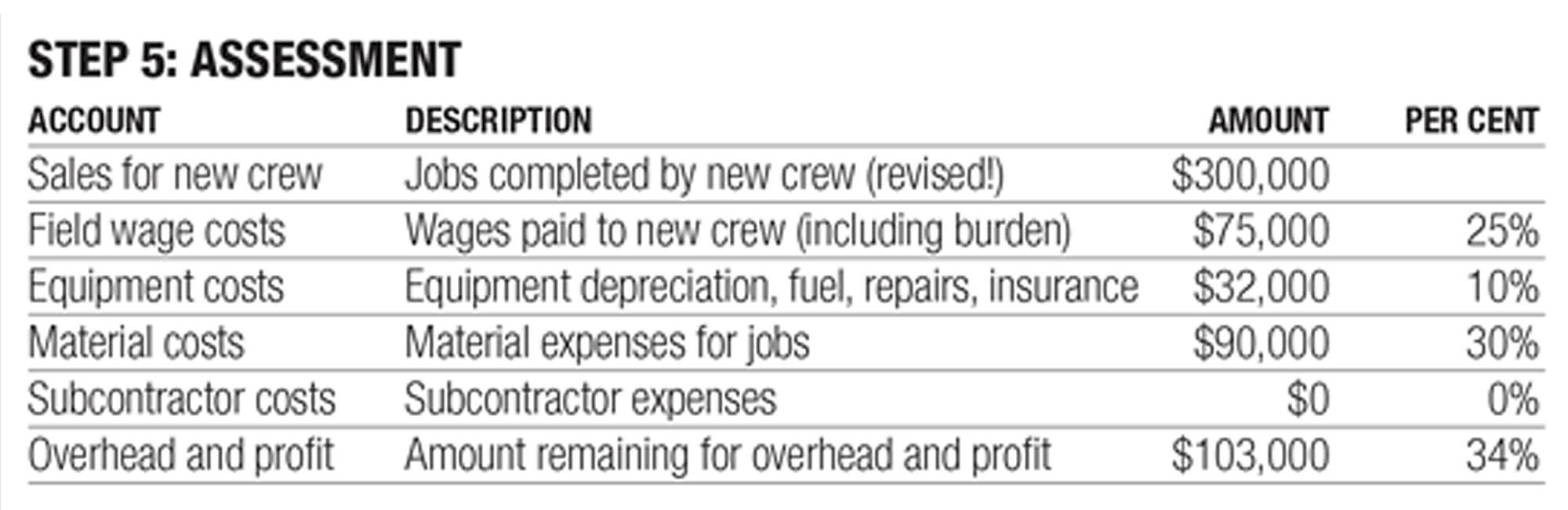

Step 5: Assess the new plan

Dan can use his material numbers from last year to help him predict whether his plan is going to work using just the numbers for his new crew.

Dan shouldn’t like how this is shaping up. His labour and equipment are significantly higher than his current averages. Last year, he had 30 per cent of his sales left over for overhead wages (10 per cent), expenses (10 per cent) and profit (10 per cent). With his new crew, he’s showing only about half of that number, 16 per cent, left over.

The short answer is that an additional $200,000 in sales is not going to cut it. He needs to sell more work for this crew to continue to grow his business as profitably as it is now.

Step 6: Make a new plan

The fastest way to give Dan a good forecast of what his new crew should do to make a profit is to use his labor ratio from last year. Labour ratio is the percentage of sales spent on field wages. (In this example, we are including payroll taxes, etc. to simplify the example. Be sure you understand which ratio you are using). Last year his labour ratio was 25 per cent. So, to get a good sales goal for his new crew he simply divides their wages ($75,000) by .25 (25 per cent, his field labor ratio). $75,000 divided by .25 is $300,000.

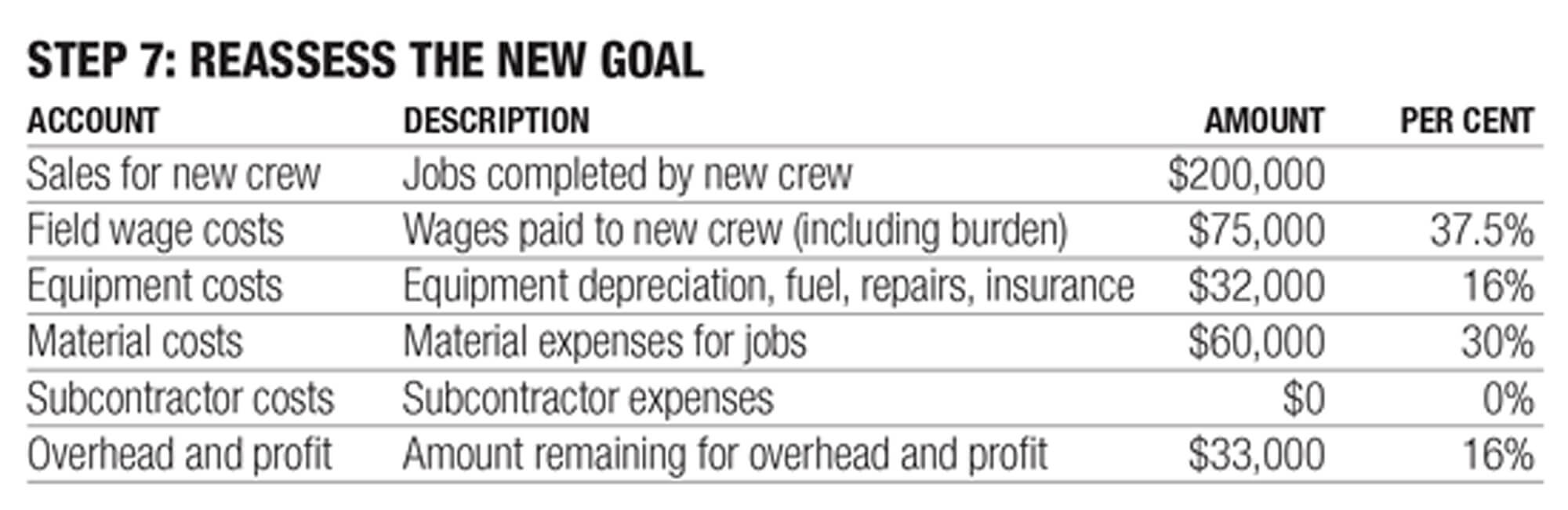

Step 7: Reassess the new goal

Dan makes a new plan. He does not forget that with more sales he is going to need more materials.

That looks a lot better. His labour and equipment will absorb their usual percentages of sales. He has increased his materials to $90,000 (a realistic figure) and he still has money left over for growth in overhead and profit. In fact, he’s now confident he can hire some part-time administrative help for the office.

Had Dan proceeded with his gut instinct of $200,000 in sales, he’d have set his business up for failure. With profit figures and labour costs from last year and a forecast budget for this year, he was easily able to calculate a profitable sales target without the stress of guessing, or any lessons learned the hard way. Can he sell $300,000 more? You’ll have to ask Dan.

Mark Bradley is president of TBG Landscape and the LMN, based in Ontario.